Education Dept. hosts second annual Production Institute

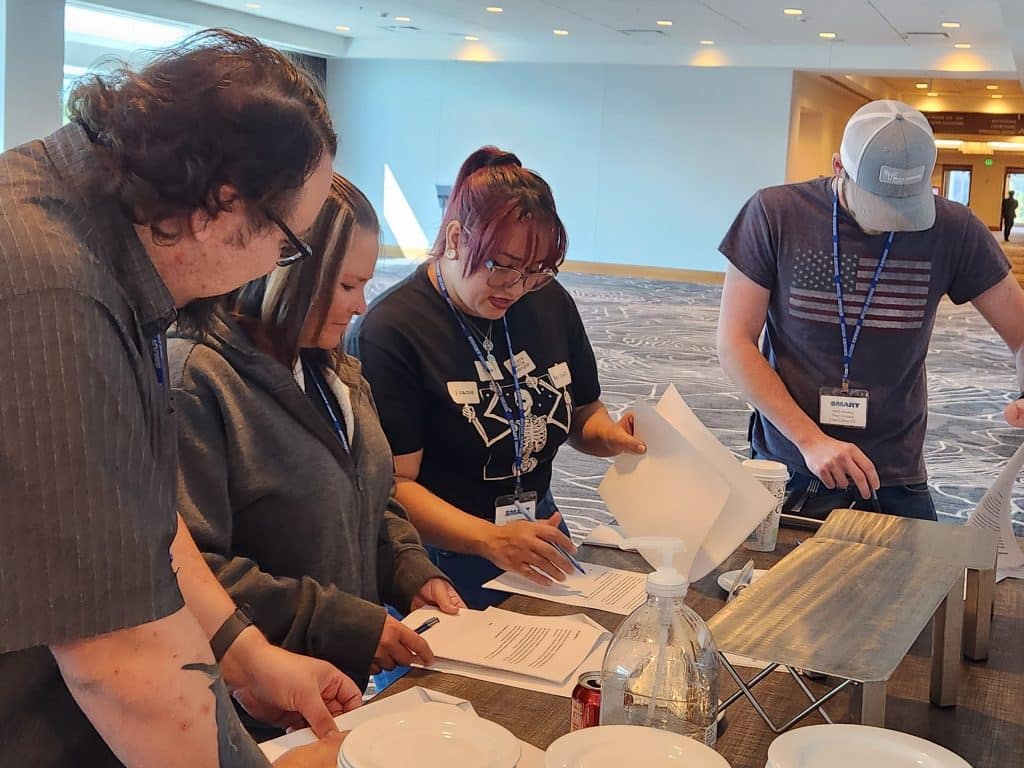

The SMART Education Department held its second annual Production Institute in Indianapolis, Ind., during the week of September 9th — bringing SMART production members and leaders together to build knowledge, skills and camaraderie, and to strategize for the years ahead.

The Production Institute is a three-year, progressive-format class, with attendees from last year advancing to the second round of courses. A new first-year class attended this year, along with the returning 2023 group.

All classes included production-focused content in the core areas of collective bargaining, steward training, organizing and labor history. Attendees also learned about more timely issues in daily breakout sessions on topics such as labor/labour law updates, the open shop agenda and Project 2025, a MEMO focus group, bias and belonging, and the production salting program. Through interactive exercises, attendees were able to apply their knowledge and develop their skills while also getting to know their peers from across North America.

New Representatives class helps latest crop of SMART leaders develop skills

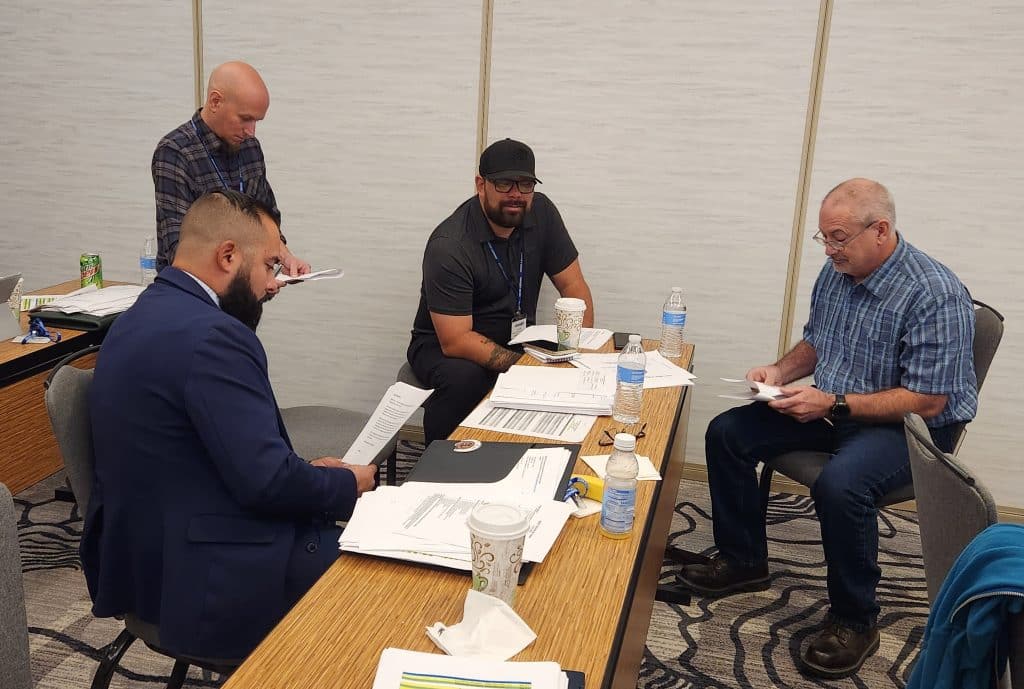

Newly elected and appointed SMART representatives traveled to Linthicum Heights, Md., during the week of September 16th, 2024, to build bonds and learn from one another in the SMART Education Department’s New Representatives I class. The new representatives worked in different groups on activities associated with topics like member misconduct, jurisdictional disputes, contract administration, pre-job meetings and crafting local union meeting reports. In addition, participants built a leadership growth plan to identify areas they would like to develop more as leaders and created specific goals around each item to help them grow throughout their careers.

Education Department hosts class on so-called “right to work” to boost member engagement, organizing

The SMART Education Department held its new “Right to Work and Member Retention” class in Detroit, Mich., during the week of September 30th. The class focused on the open shop movement, the impact of so-called right to work, strategies for improving membership retention, and the critical role that union leaders play in maintaining local union power.

Twenty-three participants from across our union worked together to problem solve and create action plans for their respective locals. The class also took time to celebrate the repeal of Michigan’s right-to-work law and the role that Michigan Locals 7 (Lansing), 80 and 292 (both Detroit) played in that process.

“Everyone’s hard work will help strengthen our union!” said SMART International Instructor Richard Mangelsdorf.